『てのしま』主人 | 日本料理アカデミー正会員

1976年香川県丸亀市生まれ岡山県玉野市育ち。立命館大学卒業後、株式会社菊の井に入社。

2011年上海万博にて『料亭 紫

MURASAKI』(日本産業館内)の料理長として赴任。2011年菊乃井本店副料理長就任、2015年菊乃井赤坂店渉外料理長就任。菊乃井主人村田吉弘氏に師事し、シンガポールエアライン機内食の開発やJR西日本『瑞風』のメニュー開発、国際会議や首相官邸での晩餐会での料理を担当。17カ国以上で和食普及のためのイベントに携わる。また、日本料理を学びたい外国人のための制度作りでは京都府と共に尽力した。

料亭における修業は「追い回し」と呼ばれる雑務担当のポジションから、「八寸場」、「焼き場」等、順を追って技術を習得し、一歩一歩昇格していきます。「花板」とよばれるお造りを担当する板前が修行のゴールと思われがちですが、実は煮炊きものを担当する「煮方」こそ、店が伝承してきた味を司る最も重要なポジションです。

その「煮方」の仕事で一番大切なのが“出汁をひく”こと。僕も修業時代に「煮方脇」と言われる「煮方」の助手を担当していたころ、毎朝、先輩が来る前に昆布出汁を引いて、鍋から昆布を取り出し、かつおを加える前までの状態にまで仕上げておくのが日課でした。

©︎ Ichigo SUGAWARA / TOKYO-GA

毎日昆布出汁を飲んで、その状態を確認する。しかし、はじめのうちは、昆布のうま味が十分に出ているかどうかの判断がつきません。かつお節やほかの出汁素材と合わせると、誰でも美味しいと判断できる味になるのですが、昆布出汁の風味は淡く儚く、昆布だけの状態で味を見極めるのは非常に難しいのです。それでも毎日ひたすらその味を確認していくうちに、昆布出汁の風味の良し悪しの判断がつくようになってきます。

今から15年ほど前、修行先の料亭「菊乃井」の師匠、村田吉弘氏に従い、海外へ行くようになったころ、初めて昆布出汁を試飲したシェフたちはその味をfishy(魚臭い)だと言い、あまり好みませんでした。今や世界が注目する「出汁のうま味」ですが、当時は全く評価されていませんでした。つまり、味覚とは後天的なものであり、出汁のうま味を美味しいと認識できるようになるには、然るべき訓練が必要なのです。

©︎ Ichigo SUGAWARA / TOKYO-GA

僕は普段から料理に応じて、意識的に出汁を使い分けています。昆布とかつおの一番出汁はもちろんのこと、いりこ、肉やジビエ、甲殻類など、また動物性だけでなく根菜や豆など野菜出汁も使います。ただ、どんな料理にも昆布出汁の旨味をベースにさまざまな組み合わせで料理を構築しています。その理由は明快です。昆布のうま味は全ての出汁食材の中で、圧倒的に強く、際立っているからです。しかもその風味は、穏やかで組み合わせる食材を生かし、支え、引き立てるのです。

昆布という文字が日本の歴史書で初めて登場するのは西暦760年、奈良正倉院に保存されていた古文書です。しかしながら、日本料理の出汁に適した昆布が取れるのは北海道の限られた地域だけです。それほどまでに産地が限定的、かつ遠隔でありながらも、昆布出汁が永く愛され、現在まで継承されてきたのは、そのうま味が日本料理にとって欠かせない味わいだったからでしょう。

日本料理は諸外国の料理と比べ、油を使わない分、油脂の代わりにうま味をもって満足感を醸し出す料理といえます。出汁における昆布は日本の国民性に似て、決して表だって主張するのではなく、全体の美味しさを支える縁の下の力持ちのような存在。どの料理にもその姿は見えないけれど、しっかり土台を支え、多様な素材と力を合わせて、日本料理の奥行きを穏やかに語りかけているように感じます。

©︎ Ichigo SUGAWARA / TOKYO-GA

そんな大切な昆布が近年、多くの魚介類同様に減少の一途をたどっています。とりわけ天然の真昆布はこの2年、水揚げゼロという壊滅的な状況に陥っています。急速に進行する地球温暖化、沿岸プランクトンの減少、過剰な漁獲などさまざまな要因が挙げられますが、その理由ははっきりとはわかっていません。

昆布がなくなると、日本料理そのものの存続危機に直結することは間違いなく、現在、日本料理人の間では昆布減少に歯止めをかける対策と同時に、昆布にも頼らなくても成立する日本料理のありかたを考えていく必要もあるのではないか、という議論も起こっています。

日本人が継承してきた素晴らしい“出汁文化”を次世代に繋げるためにも、味覚を訓練し、自分で引いた出汁を使った料理を週に1度でもご家庭で作ってほしいというのが、今の僕のささやかな願いです。

©︎ Yoshihiko UEDA / L’art de Rosangin

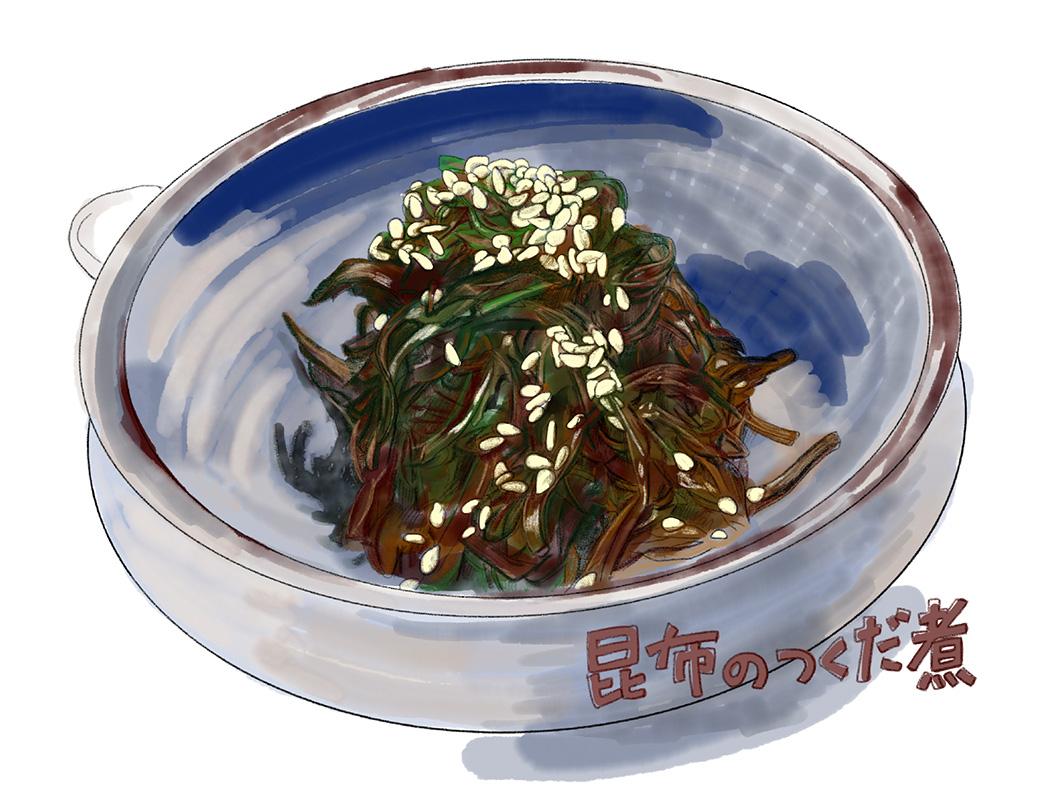

今回は家庭で気軽に昆布を取り入れて頂けて常備菜になるおかずと出汁をとった後の昆布で作れるつくだ煮をご紹介します。

Illustration ©︎ Yuka OHTA

Illustration ©︎ Yuka OHTA

Owner of ‘Tenoshima’ and Full member of the Japanese Culinary Academy

Born in Marugame (Kagawa Prefecture) in 1976, and raised in Tamano City (Okayama Prefecture). After graduating from Ritsumeikan University, he started to work in Kikunoi. After considerable training, in 2011 he was appointed as the head chef of the Japanese restaurant ‘MURASAKI’ in the Japanese Industry Pavilion at the Shanghai World Expo. In the same year, he became sous-chef of Kikunoi’s main restaurant, and in 2015 became the International Liaison head chef of the Kikunoi Akasaka restaurant. Under the guidance of Mr. Yoshihiro Murata, Kikunoi’s owner, he was in charge of developing in-flight meals for Singapore Airlines, developing menus for JR West rail’s "TWILIGHT EXPRESS MIZUKAZE", and preparing food for international conferences and banquets at the Prime Minister's official residence. He has been involved in events to popularise Japanese food in more than 17 countries. In addition, he worked with Kyoto Prefecture to create a system for non-Japanese who want to study Japanese cuisine.

An apprenticeship at a Ryotei level of Japanese restaurant starts from the miscellaneous duties-focused position called ‘Oimawashi’ (literally ‘running after’, actually it means general supporting tasks such as dish washing and cleaning), followed by ‘Hassun-ba’ (preparing appetizer dish) and ‘Yakiba’ (grilling) etc., with apprentices learning the techniques and being promoted step by step. Many believe the position of ‘Hanaita’, the main chef in charge of preparing sashimi, is the ultimate goal, yet in reality the ‘Nikata’, who is in charge of the stewing and finishing the taste of the Dashi, is the most important position, as they control the flavour that the restaurant has imparted to them.

The Nikata chef’s most important role is to ‘make the dashi stock’. During my apprenticeship when I was the Nikata chef’s assistant, which they used to label as the ‘Simmering Sidekick’, I had a daily routine. Every morning before the more senior staff arrived, I would make the kombu dashi (kelp stock), take out the kombu from the pot, and ensure it was ready for bonito to be added.

©︎ Ichigo SUGAWARA / TOKYO-GA

You drink a little of the kombu dashi daily to check its condition, but at first you are not able to determine whether the depth of flavour of the kombu is sufficient or not. When combined with dried bonito and other dashi ingredients, anyone would judge the taste to be delicious, but the flavour of kombu dashi is light and fleeting, and it is very difficult to determine the taste with kombu alone. However, by checking the taste daily, you become able to judge whether the flavour of the kombu dashi is good or bad.

Accompanying Mr. Yoshihiro Murata, the master of Kikunoi where I trained, when we first started going overseas around 15 years ago the chefs who tasted kombu dashi for the first time found it ‘fishy’ and did not like the taste very much. The ‘Dashi’s Umami’ is now attracting worldwide attention, but at that time it was not well regarded at all. In other words, it is an acquired taste and proper training is needed to be able to recognize the taste of dashi as delicious.

©︎ Ichigo SUGAWARA / TOKYO-GA

I usually consciously use the dashi according to the food I am making. We of course use the best kelp and bonito dashi, as well as sardines, meat, game, and shellfish etc., but in addition to meat products we also use vegetable dashi from root vegetables and beans. However, whatever the dish, we create various combinations of dishes based on the flavour and umami of kombu dashi. The reason for this is clear. It is because the kombu’s umami is overwhelmingly strong and stands out above the other ingredients in the dashi. Moreover, its flavour makes use of the gentle combination of ingredients to support and enhance it.

The word ‘Kombu’ first appeared in Japanese history books in 760AD, an ancient document preserved in Nara Shosoin. However, kombu suitable for Japanese dashi is only available from a limited area of Hokkaido. Although the cultivation area is so limited and remote, kombu dashi has been well-loved for a long time, passed down from generation to generation because its umami flavour is surely indispensable for Japanese cuisine.

Compared to other countries, Japanese cuisine does not use oil, so it can be said that satisfying dishes are created with umami rather than oil and fat. The kombu in dashi is understatement, which is similar to the national character of Japanese people, and unsung hero that supports the overall deliciousness. I cannot see it in any dish, yet I feel that it firmly supports the foundations, combining its power with various ingredients, and gently speaking to you about the depth of Japanese cuisine.

©︎ Ichigo SUGAWARA / TOKYO-GA

In recent years, this important kombu has been in steady decline, like many fish and shellfish. In particular, natural kombu has catastrophically seen zero catches over the last two years. There are many factors in play, including rapid global warming, declining coastal plankton and overfishing, but the exact reasons remain unclear.

If kombu disappears, there is no doubt that this will lead directly to a survival crisis of Japanese food itself. As well as measures among Japanese chefs to stop the decline in kombu, there is also a debate about whether it is necessary reconsider and re-establish Japanese cuisine without a reliance on kombu.

In order to pass on the wonderful ‘Dashi Culture’ inherited by the Japanese people to the next generation, I would like people to train their taste buds and cook their own dishes using homemade dashi, even just once a week. This is my modest request.

©︎ Yoshihiko UEDA / L’art de Rosangin